(Hair)

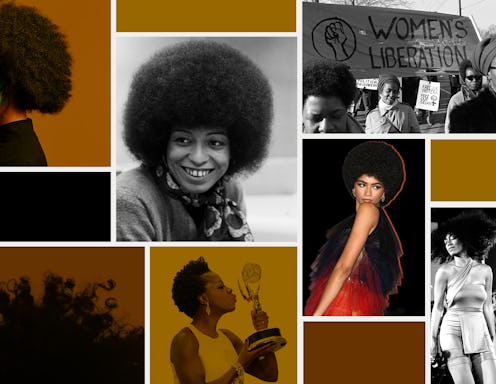

The Complicated & Powerful History Of The Afro

How it started and where it is today.

Today, we Black people are celebrated for our intricate braiding techniques, dance moves, poetic speech, singing voices, political and athletic capabilities, fashion, and so much more. But it wasn’t always like this. In the times of the slave trade, Black people were forced by white owners to suppress their talents and beauty in efforts to not draw attention to themselves. It was one of the many ways we were dehumanized. When slavery ended in 1865, European beauty standards still dominated and continuously proved to be a prerequisite for attending good schools, landing specific jobs, and being accepted into certain social circles. Back then, straight hair was the norm and entrance into society. People created hot combs, hair relaxers, and invested in all manner of straight hair to appease society and get further in their careers and lives.

Fast forward to the 1960s: Black women slowly started trading in their relaxers and weaves for their natural coils, curls, and waves during the original natural hair movement, “Black is Beautiful.” The movement was about embracing the beauty of skin tones, facial features, and natural hair — allowing Black people to reconnect to their roots. The afro, a voluminous hairstyle that takes up space, played a large role in reclaiming that power and embracing our natural traits. In fact, it was a pivotal symbol in saying, “I’m Black and I’m proud,” the iconic tagline of the Black Panthers — a group of Black and brown men and women who preached armed self-defense against police brutality.

The Journey Of The Afro

With political activists like Angela Davis, Huey P. Newton, and Jesse Jackson all wearing afros while fighting oppression, the Civil Rights Movement helped transform society’s view of the afro from an “unkempt” look to a political statement, solidifying the hairstyle as an image of Black beauty, liberation, and pride. “The afro became the birthplace of the natural hair movement,” says Michelle O’Connor, Matrix global artistic director. “It changed the status quo and enabled us to normalize hair that wasn’t chemically straightened or pressed.” This was a phenomenon at a time when straight hair directly correlated to professionalism and acceptance.

Although the ‘60s and 70s celebrated the fro, straight hair still ruled elite social circles and rooms of power. “When you aren’t in a position of power, it causes you to feel like you have to look a certain way, not only to be accepted, but respected,” says Maude Okrah, the co-founder of Black Beauty Roster, an organization that looks to amplify the work of Black beauty artists in television, film, and editorial. As much as Black women and men wore their hair in fro’s, the reality is, from the ‘60s to late ‘90s, texture education simply did not exist in most cosmetology curriculum. The interest and importance to teach non-Black hairstylists how to work with textured hair fell flat for years — creating a narrative that Black hair was complicated, irregular, and undesirable.

Many Black women opted to play the game and invest in relaxers and straight weaves to appear more professional and “deserving” of certain lifestyles and careers. Of course this didn’t apply to all Black women at the time, but instead a large majority. In fact, it wasn’t until the early ‘00s where embracing natural hair started to become popular again thanks to ‘90s Black sitcoms like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air where Ashley Banks (played by Tatyana Ali) is seen parading around in brushed-out curls, bonnets, and natural styles; or braids and detangled curls seen on Tia and Tamera Mowry in Sister, Sister.

In the early aughts, Black hair bloggers on Youtube and Instagram started popping up, producing tutorials on how to care for and style texture hair — further increasing awareness. When you understand the images portrayed in media are small snapshots of normalcy, you realize why representation across all screens and platforms matters. “As more people learn about textured hair, and see more and more imagery of it, the more people are able to grasp that it’s normal and considered beautiful,” Okrah tells TZR.

These Black sitcoms and women in power that showcased natural hair made for a clear foundation for The CROWN Act, a law banning race-based hair discrimination that launched in 2019. The law gives women of color the freedom of choice to decide on how they want to wear their hair, whether that’s natural, straight, braided, or weaved, without backlash, denial of opportunities, or intense questioning of their ties to their heritage. With the CROWN Act, the afro challenges the societal norms around what hair should look like. “It speaks politically to the push back of what is deemed acceptable within mainstream society,” O’Connor continues.

Unfortunately for Black women, hair will always be political. We choose to weave or straighten our hair and are accused of assimilating. We braid our hair and are praised for honoring the diaspora. Having versatile hair becomes a double-edge sword, great for the wearer, but open for public scrutiny. For Black men and women, our appearance is often seen first, rather than our talent or character, and can drastically impact how far we get in careers and how others treat us. The afro takes all of that into consideration and stands up to society, refusing to give into all the outdated rules.

What The Afro Represents Today

On one hand, today, the afro is often seen as cool, confident, and powerful in our community. It has appeared at the Met Gala, the Oscars, and high fashion runway shows. Celebrities like Solange, Zendaya, Viola Davis, and so many more influential Black women in the space have fully embraced the look. The problematic reality is that, even after all this time, there is still some negative connotation that it represents resistance, militancy, and unprofessionalism. It’s the reason that Black and brown women are still being fired from jobs and asked to leave schools due to their hair choices.

“Today we have more traction and interest in wearing multiple styles,” says Diane Da Costa, author of Textured Tresses and one of the founding members of the National Hairstyle and Braid Collation, a group aimed at educating the consumer to love, embrace, and preserve their natural crown. “We do understand and love our hair, but there are still a handful of women and young girls struggling to embrace and love their texture. It’s an incomprehensible reality that we are still fighting for in a different way.”

In terms of styling, the difference between the ‘60s afro and 2022 afro is in the texture, what it represents, and the brands and products that cater to it. “There are more products and more love [and fascination] for big hair in all its glory,” Da Costa continues. “Today it’s not as big of a political statement as it is our right, now.” It’s the empowerment and choice that we have today that makes the afro really cool while still paying tribute to the symbol in rebellion against a system that so clearly was not created to include us.