(First-Timers)

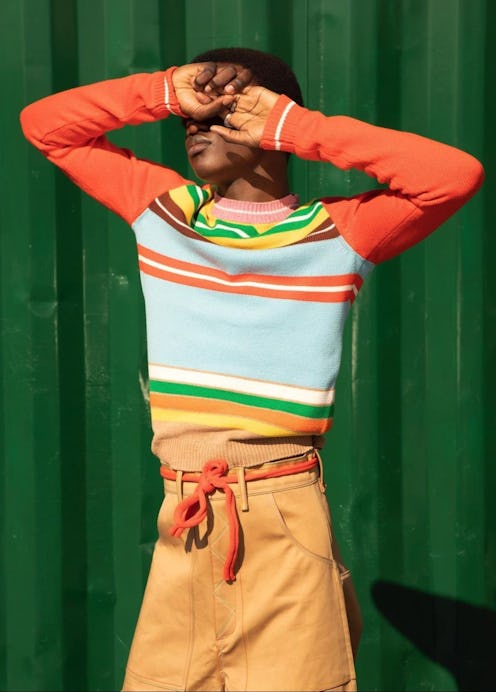

Black Boy Knits' Jacques Agbobly Wants To Knit You A Hug

There’s love in every stitch.

In the weeks leading up to New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2023, TZR will be showcasing a few new names on the show line-up. From emerging young designers to cult-favorite brands, these are the labels to have on your radar. Watch this space for more.

When the pandemic forced Parsons School of Design students out of the classrooms and into their apartments, Jacques Agbobly, in the spring of their senior year, was more relieved than anything. Exhausted by the constant grind of the renowned institution’s courseload and training to enter a notoriously competitive industry, the time to reevaluate just what it was that drew them to fashion in the first place was key. Those months in solitude reflecting on their craft outside the realm of their esteemed university’s demanding schedule set Agbobly on a path that would lead to building their brand Black Boy Knits. Now, only two years later, they’re debuting it at New York Fashion Week this September.

But first, let’s talk about the name, which Agbobly chose as a way of boldly stamping their identity on the clothes. “I think as designers, especially today, we don’t have any choice but to put ourselves in the work that we do,” Agbobly says. “That’s what makes us unique, and at the time I was launching it, I was in a weird situation where I was really tired of fashion, but I also wanted people to know who was making this. So it was really about putting myself in the work: I am a queer person, I am Black. My experience is as a queer, Black person and I often pull from that.”

Agbobly first felt the allure of fashion growing up in Lomé, Togo. Having spent a lot of their childhood in their grandmother’s house, part of which doubled as a busy studio space for the seamstresses and tailors to whom she rented, it makes sense that the designer came to naturally associate the art of making clothes with home. From their spot under the table, Agbobly watched in awe as the women worked, mesmerized by the rhythm of their movements and the way the fabrics transformed in their hands. Looking back, they figured that seeing so many women working with their hands in the studio space, and also braiding hair (another trade in which the women in their family were trained), caused Agbobly to feel naturally drawn toward knitwear. Shaping the garments by hand that way has always felt warmer, more personable, and less mechanical to them. It’s that warmth that they want to infuse into the garments at Black Boy Knits; the pieces are meant, per the item descriptions on the website, to “hug the body perfectly.” The tank tops up on the site are made-to-order, with a note that customers can expect Agbobly to follow up about further customizations after purchases are placed.

On a call from their New York City apartment, Agbobly laughs as they apologize for the increasing volume of meows from their cats in the background — it seems only fitting for a knitwear designer to be surrounded by felines, toying with pieces of stray yarn or string strewn about their quarters. As lighthearted and jovial as Agbobly sounds hushing their pets and squeezing in time for this call as they’re prepping for fashion week, they are still essentially a one-person band and laser focus is crucial. They were a finalist of the 2022 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, which showed them the value in having some additional help. Though they’ve taken on a few interns this summer to provide limited assistance in an operational capacity, all garments pass directly through Agbobly’s hands.

With their home in Togo having been a partial studio space, a love for fashion is in the textile artist’s DNA. But a knack for knitwear in particular was something Agbobly had to work to cultivate.

“I gravitated toward knitwear because it was very malleable, it almost felt like I was building a sculpture,” they say. “I took a knitting class in school, and I really just stuck with it. Fun fact: I actually failed my first knitting class — well, not failed, but almost failed,” Agbably remembers. “As an African immigrant, failure is not an option! I got a D.” Agbobly recalls that alongside their first knitting class, they were working three jobs just to pay for school. “When you’re knitting you have to dedicate time to do it. It’s not something you can crank out and turn it in. I just never had the time.”

Disappointed with themself but determined to make up for it, they decided to not only take that class again but to submit fully to their self-imposed challenge by taking on three knitting courses the following semester.

“Almost my entire work that semester was knitwear, so I just became obsessed with it and really fell in love with it in trying to prove to myself that I could do it,” they say.

Their talent is not something they’ve necessarily felt extra pressure to prove to their family, who have long been supportive of their work. They moved from their home in Togo to Chicago in 2007, when Agbobly was 9 years old. It wouldn’t take long for them, even as an elementary school student, to realize fashion was their calling.

“As a young immigrant kid, you're put in those after school programs because they really want you to develop a community,” Agbobly says. “In those sorts of spaces the question they would always ask was ‘what do you want to be when you grow up?’” Being prompted to contemplate their eventual career choice cemented over time that the end goal was working in fashion design. In their household, “closed mouths don’t get fed,” so they were always vocal about their dreams and said their family steered them in the right direction. They found themself at Parsons, where they felt not totally adrift — anchored by a cohort of largely Black students that organically came together, pulling all-nighters in a studio space with Beyoncé playing in the background — but definitely somewhat out of place.

“It was a very interesting thing for me, as an indigenous, queer, immigrant person, being in a space that was predominantly full of other immigrants but other immigrants that came from like, wealth, it was a culture shock,” Agbobly notes, explaining that while they had no choice but to put in the time to pattern, knit, and sew all their garments by hand, many of their fellow students had the resources to have their pieces outsourced. “I think a lot of the work that I was doing was heavily misunderstood, by a lot of my teachers, a lot of my peers — and I also didn’t understand what I was doing. But it was the community of mainly Black folks that I surrounded myself with who continually uplifted me in those moments that showed me the communal aspect of fashion.”

Indeed, leaning on community is what helped launch Black Boy Knits at the height of a global pandemic. After navigating through their burnout, the designer stripped back their concept of everything they’d learned about the craft and the industry in school, and what remained was “that feeling of why I started in fashion: it was about custom clothing, reaching community.” And when that ideation process began, they touched base with a former professor who pulled resources together to get Agbobly a studio space for a year, giving them both a physical space but also the mental breathing room to create freely.

“When you’re in school there’s this very concentrated idea of the industry, and it’s scary,” they say. “It’s cutthroat and I never saw myself in that space. It was through the process of releasing my own work that I started sort of developing not only a clientele but a sort of community around my work. I think through that, I've fallen in love with fashion on my own terms, which has been beautiful.” In a studio all their own, without the demands of regular assignments, Agbobly thrived.

“It allowed me to see what is special about me, what I want to do and what I want to put out into the world, versus what other people want me to put out into the world,” they say. “When you’re in school, you get all these assignments that are like, ‘solve this world issue.’ And I'm like, I don't have to do that. [laughs] That’s something that I learned outside of school, because it can feel too far out when you’re asked to solve world issues but I feel like we can solve things one garment at a time!”

Their “one garment at a time” philosophy with Black Boy Knits, placing the craft above all else, is part of what makes them stand out as a brand in an increasingly crowded knitwear market: locally sourcing the best fabrics in the U.S., making the pieces all themself, and avoiding the churn that gives the industry its bad reputation as a contributor to environmental degradation, is certainly one way to move the needle. Both the sustainable ethos and the clear dedication Agbobly had to their work caught the eye of IMG’s director of designer relations and development, Noah Kozlowski.

“I first discovered Black Boy Knits on Instagram and became obsessed,” Kozlowski says. “Little did I know Jacques was also trying to get in touch with me! I was drawn to the brand aesthetic, the fresh look of their collection and the fun custom color ways. I was super impressed to learn that Jacques hand knits every item and sources fabrics locally in the U.S.”

Seeing this new wave of talent including Agbobly, which puts ethics and inclusion at the forefront of their businesses, is inspiring and exciting for Kozlowski. While knitwear becomes more and more popular, he believes it’s brands like Black Boy Knits creating one-of-one pieces that will continue to rise to the top, as their quality speaks for itself.

“The fact that Jacques is literally hand making every garment and spends up to 10+ hours per piece commands respect,” Kozlowski says. “The custom work is very special and the price point is rather accessible given the amount of personal attention and detail that goes into every item Jacques is knitting. ... what Jacques is doing is different and there is nothing more special than that perfect sweater. Black Boy Knits are handmade to measure with a lot of love. It’s no wonder why Jacques was recently hired by Converse to help with their textiles development. I cannot wait to watch where they go and know this debut NYFW season will be big.”

Despite their elation at being included in the NYFW lineup, Agbobly wasn’t initially so sure about rising to the opportunity. It was again the support of their community, that reliable wellspring they’ve drawn from in times of uncertainty, that pushed them to accept.

“I was still debating, ‘am I ready for this?’” they say, recalling feeling stressed about their capacity to put out work as a team of one on such a big stage. “My mentor was the driver in allowing me to see this and he told me: Any opportunity you get to show people your work and what you do is an opportunity you shouldn’t miss. And I really took that to heart. It’s been a great experience just to see the inner workings of everything. I’m really excited and looking forward to it!”

The line Agbobly is presenting is a mixture of many influences, but a large overarching theme is the celebration of their Togolese heritage. Titled “Togo Vivina” which translates directly from Ewe as “Togo feels so good” (and more colloquially, Agbobly says, as “life’s really great in Togo”) the collection is about going back to their roots and feeling at home.

Everyday elements of life in Togo, things like the drinks they’d have and games they used to play, loomed large in their mind as they put the garments together. Agbobly shares that fashion week fanatics can expect to see some super fun prints that invoke the archetypes of their Togolese culture in the show. One piece that they feel particular affection for is a rebuilt version of the school uniform they used to wear.

The forthcoming collection’s ethos is in perfect alignment with what they’d consider to be Black Boy Knits’s mission statement: bringing joy, and bringing Togolese heritage and craft to the western luxury marketplace. “Couture” as a term, in Agbobly’s experience, comes with “all these technicalities” determining whether certain work qualifies, or is excluded, in the world of high fashion. Casting off whatever baggage or constraints that others might associate the term with, Agbobly is proud to label the work couture themself.

“There are a lot of crafts I grew up with that in today’s world would not be considered ‘couture,’” they say. “I think it’s because we’re not based in Europe. But just shedding light on all the wonderful crafts and the richness that comes from West Africa, specifically Togo, is something that I really look forward to doing.”

Also on the horizon for the brand is a full size collection slated for later this year. After putting out small capsules the past two years since getting started, Agbobly is looking forward to “telling a full story” as opposed to the “snippets” they’ve been releasing. And as they grow and scale their business, they aim to bring it all back to their beginnings by working with artisans in Togo. Being able to provide a livelihood for people in their native country would mean everything for Agbobly.

“It’s a big responsibility and I feel like Togo, because we’re such a small country, people don’t really know about us,” they say. Their vision is that the line will present an opportunity for Togo to be seen, so that “people can start understanding us, learning our history, and hopefully in the process just creating beautiful things.”

With the knowledge that the brand is rooted in their strongest foundation — home — Agbobly hopes to welcome wearers inside to share in that warm, cozy feeling of being swaddled in love. Home is watching quick hands weave from under a table in Lomé, commiserating with a group of overworked fashion students, waving pets away in a city apartment; it’s a place — sometimes many different places even for one person — but it’s also a feeling. Wrapped in the custom handiwork that an artisan has poured hours of their life into, the craft they have honed in one way or another since childhood, it’s hard not to feel cared for.

We may receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.