(Fragrance)

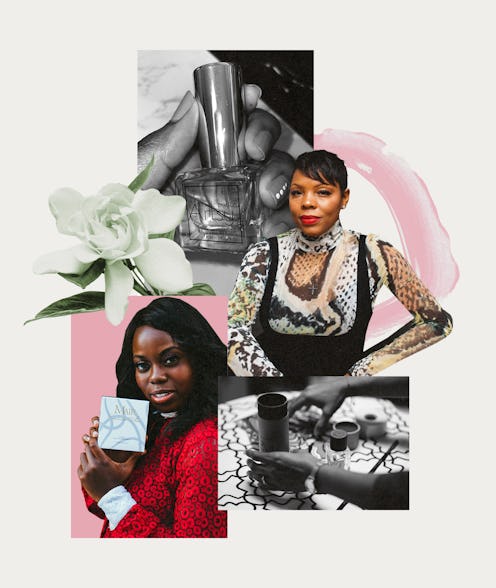

Black Women & Fragrance: A Love Story

Recognizing the power of the Black female perfume lover.

If you’re not already an ardent beauty lover you may not realize it, but fragrance is having a moment, with 2021’s first quarter marked by a 45% increase in sales. As it happens, so are Black consumers who, according to a September 2021 Forbes report, “represent $151 million [spent on women’s fragrances, out] of a $679 million industry.” Black perfumers are also making waves in the fragrance space — despite the number of them remaining disappointingly low compared to the rest of the predominately white industry — with brands like MAIR and KIMBERLY New York leading the way. Black women especially are making their passion for fragrances known, both professionally and personally, effectively reshaping the understanding of who the modern fragrance customer is — and who gets to have a say in this lucrative sector of the beauty market.

Aside from the talent formulating the juice, if you’re looking at perfume marketing over the last 60 years or so, Black women have been only marginally represented. Perfume ads have mostly starred white models, with some breakthroughs for Black models along the way, such as in the 1970s with Revlon’s Charlie ads, Beverly Johnson posing for Chantilly in 1980, and a Black model fronting Faberge’s Tigress in 1983.

In the 2000s, Beyoncé sashayed for Emporio Armani’s Diamonds and exuded star power for Tommy Hilfiger’s True Star. And these days, YSL’s got Lenny and Zoë Kravtiz on lock promoting Y and Black Opium. So while it’s not to say that recognizing the Black consumer or having a Black figure in perfume marketing has never happened, it still remains too few and far between. (Albeit, progress is occurring. See as of late, Jourdan Dunn for Mugler’s Alien and Adut Akech swearing-in Valentino’s Born in Roma).

A deep dive into the social media accounts (#perfumeTok anyone?) of Black content creators and Black-owned brands reaffirms the fact that Black women have always had a deep and abiding connection with fragrance — a connection that spans decades and continents across the diaspora.

And so, in knowing this, how can there continue to be so much under-representation for Black women within and around the fragrance industry?

The State Of The Modern Black Perfumer

As the founder of her eponymous brand MAIR, Mair Emenogu recognizes the responsibility of being one of the few visible Black perfumers working today. Currently, her ethereal line of “soft, light” perfumes is the only Black-owned fragrance brand sold at Macy's. “I’ll tell you, most are shocked when they find out I’m the one who created the line,” she says. “It reinforces the idea that representation matters.”

The lack of Black talent in perfumery really came to light in 2020 in the midst of Black Lives Matter and the long-overdue conversations that resulted surrounding diversity and inclusion in the beauty industry. But it’s important to note that Black-owned fragrance founders have been developing their own lines as outliers for quite some time now.

Take Chavalia Dunlap-Mwamba, the founder and nose of gender-neutral line Pink MahogHany. After starting the brand in 2005 — first at Texas flea markets before pivoting to Etsy and eventually her own e-commerce platform — she is now a doyenne of Black-owned perfumes, a catalyst for peers and customers (many of whom are Black and people of color) alike for representation in an overwhelmingly white industry. “I have received a lot of love, mainly because [for so long] PM [was] such a rarity,” she says. “And I actually own the brand. It’s not like I’m putting my name on a fragrance and a filling house formulates [it].”

Dunlap-Mwamba, like many other Black perfumers, is self-taught. This is mainly because the chance to be classically trained at an expensive school like Parfumerie Fragonard in Grasse, France — the perfume capital of the world — eludes aspiring Black students the most. (Though times are a-changin' as Chris Collins, founder of the only Black-owned cologne sold at Bergdorf Goodman, studied in Grasse, and Alexia P. Hammond’s Eat.Sweat.Undress hair perfume is manufactured there.)

But in the last 16 years and counting, Dunlap-Mwamba has recognized that there's artistic freedom to regale in as an anomaly in her business. “I think the Black perfumer’s perspective is raw because the majority of us are self-taught,” she says. “We go by intuition, how we feel about a particular note. We also don’t have aversions to certain notes due to conditioning. So I think that allows us, self-taught perfumers, to have an openness and ability to connect and treat fragrance as an art form, too.”

Fellow autodidact Kimberly Walker created her niche perfume line KIMBERLY New York (KNY) after a decade as a luxury fragrance sales manager at a department store, during which she never had the opportunity to sell fragrances by Black talent. She did, however, hear from clients directly about what they felt was missing on the perfume counter.

“Clients would regularly say ‘Everything just smells the same’ [and] I agreed,” Walker explains via email. “The market needed new [options]. Popular fragrance houses were being run by the same small group of people, and the lack of diversity showed an obvious lack of creativity.”

Fragrance For Black Women Is Self-Care

So why do so many Black female consumers continue to embrace an industry that is slow to invite more perfumers of color into the fold, or expand representation in its advertising?

“It’s the versatility that has allowed me to stay connected to fragrances,” says Kimberly Waters, the founder of the Central Harlem boutique MUSE Experiences, the only Black-owned fragrance store in upper Manhattan. (Included in the niche and indie brands she sells are Black-owned brands such as Aspen Apothecary and Swedish-West Nigerian brand Maya Njie.) “Our grooming is also a part of our pride. We will make sure, even if going through some things, that when we step out, we step out and be the best version of ourselves. I think it’s that type of culture, that as Black people and Black women, keeps us going. And fragrance plays into that.”

Dunlap-Mwamba reiterates that the bond between Black women and fragrance is centered on self-expression. “[Perfume] is a part of our self-care routine, our beauty regimen. We want to feel good about ourselves, and naturally, fragrance is a way to express that. It’s very powerful and holds so much weight in our day or look.”

Walker adds that the deep roots of a Black woman’s affinity for fragrance are largely familial. “Black women connect strongly to scents worn by matriarchal figures in their family,” she writes. Imbued throughout her nine KNY fragrances is her love for aromatics and “ingredients like allspice or ‘pimento’ as Jamaicans call it.” (Walker was born in the parish of St. Ann.) “Along with fragrant herbs like thyme and mint [that] consistently wafted from my mother’s kitchen.”

Fragrance In The Motherland

The significance of perfume in the everyday lives of Black women is also an international phenomenon with important historical context. Waters recognized this during a recent work sojourn to Senegal. After visiting the Dakar-based, Black-women-owned and operated Olfactif by TR and meeting with Marieme Soda Ba Diagne (who owns the online shop Parfumerie Bouton d’Or), Waters witnessed for herself how Black African women share a need for aromatic expression just as much as Black women in the U.S. do.

“Scent is a big part of their lifestyle,” she says. “The Senegalese like very hearty, dark notes, heavy woods, and sweet gourmand fragrances. Africans like to be smelled and to be noticed.”

Waters adds that their appreciation of scent is further intensified by deodorant being a limited resource in the region. The fact that “their scent is more so their body odor,” magnifies another emotional layer of why Black women (and men) are drawn to perfume.

“We’ve been innovative in trying to use scent in how we share ourselves with the world, or as a survival tactic,” Waters says, in reference to what she learned about Senegalese hygiene hacks. “[Black people] didn’t have access to essential oils [centuries ago], but we had the ingenuity to figure out what we could grow, and use lavender plants and certain things to enhance ourselves when we didn’t possibly feel the best. We’ve always made the best of what we had.”

The Online Community Of Black Fragrance Lovers

Taking into account the modern-day journey of a Black female fragrance lover, it’s no wonder that in 2021 fan accounts founded by Black women are exploding in popularity, often behaving as internet clubhouses to gab, trade, and catch up as aficionados do. From niche accounts like BlackGirlsSmellGood (BGSG) to “Your Fave Fragrance Auntie” aka Funmi’s TikTok, ISmellLikeChanel.Too, The CherysTv, and Perfume Fiend, as well as YouTubers like Andrea Renee, these pages are welcoming spaces for Black women to disclose why certain scents have taken up residence in their personal perfume libraries.

Black women on #PerfumeTok are not only informative but simply just a blast to watch with their creative visuals, commentary, and unapologetic Black-girls-rock mentality — a sign that updating the narrative of who’s really driving sales and fandom into record numbers needs to be recognized.

This burgeoning community feels unsurprising for Walker, given her experience interacting with shoppers one-on-one prior to launching KNY. “Fragrance lovers find joy in discussing notes and comparing newness to old faves,” she says, recalling the community she built in retail.

Waters adds that she is thrilled to see Black women creating dedicated spaces for each other to explore and partake in their shared fragrance interests. In her pre-MUSE days, social media was helpful in locating the fellow fragrance-obsessed. But, she admits, it was a smaller scale in 2012. “[That time] was like my entryway into this space, As I was trying to figure out what my voice would be within fragrance,” she says. She connected with micro-influencers and bloggers at boutique and department store events, attended Sniffapolooza, and was inspired by YouTubers, such as the late Carlos J. Powell, the Brooklyn Fragrance Lover. “Now, [the scene has] definitely grown,” Waters says. “Like Black Girls Smells Good? That didn’t exist and it’s amazing to see.”

It’s a compelling, historical, and exciting time for Black creators in the perfume sphere. The revolution is slowly but surely occurring in perfumery, social media mavens are holding it down for inclusion, and the power of the Black female dollar is likely to continue to reign.

For MAIR’s Emenogu, it’s that bigger landscape on the horizon for fragrance that will continue to inspire. “It’s surreal because it’s like, wow, we’re really doing this! We’re really pushing the needle and making noise,” she exclaims. “We’re doing it, doing well, and happen to be Black. We’re setting the precedent of doing it well. It’s a vibe.”